We all have our areas of ignorance, where we can quite accurately be called dummies. That’s not a pejorative term, but a simple statement of fact: we don’t know everything and we’re well aware of our areas of complete ignorance. John Wiley & Sons has an entire series of instructional books just for us.

Unfortunately, there is an even more dangerous state just beyond ignorance that, for the purposes of this article, we’ll call the amateur. Alexander Pope warned us about it in his 1709 poem An Essay on Criticism

A little Learning is a dang’rous Thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian Spring:

There shallow Draughts intoxicate the Brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.

Pope warns us not to “progress” from a state of acknowledged ignorance to a state of believing that we know more than we actually know. It’s not hard to imagine this danger, right? I mean, how hard could it be to captain a ship on the open sea? Or to climb a mountain? Or to rewire your house? The amateurs that actually try these things win Darwin Awards.

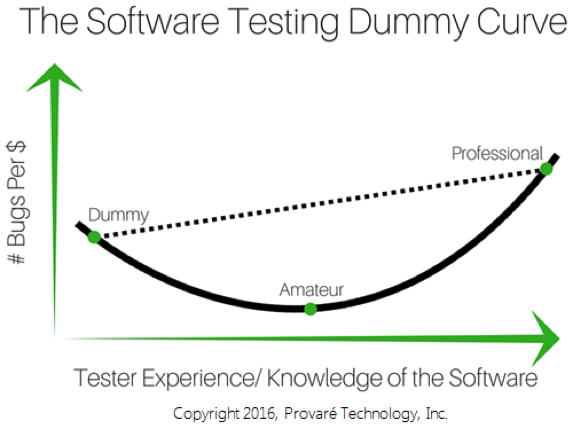

David Sandler introduced the concept of the Dummy Curve as it applies to sales years ago. According to Sandler, dummies make a fair number of sales because their ignorance forces them to ask a lot of questions. The mistake that they (and/or their employers) make is in thinking that the training that they need is knowledge about their products. But when they gain this knowledge, they talk more and ask fewer questions and therefore sell less. They become amateurs. Professional sales people, Sandler asserted, learn how to do what they used to do as dummies, only now they do it intentionally and according to a plan.

The exact same danger and opportunity exists in software testing. A dummy (i.e., a person who has no experience either in testing software or with the specific software being tested) can find a fair number of bugs. How? By stumbling around blindly and trying a lot of things out of sheer ignorance that the software designers never expected someone to try.

The exact same danger and opportunity exists in software testing. A dummy (i.e., a person who has no experience either in testing software or with the specific software being tested) can find a fair number of bugs. How? By stumbling around blindly and trying a lot of things out of sheer ignorance that the software designers never expected someone to try.

But as this dummy tester learns how the software is supposed to work, he or she will do a lot less bumbling and will begin testing the software more as it was designed. In QA parlance, they will do a lot less negative testing, shifting almost entirely to use case or positive testing. As a result, they will find a lot fewer bugs.

This makes sense, right? Surely even a struggling software developer can write software that does what it is supposed to do under expected conditions – at least most of the time. But even the best developers have their blind spots. And if there is one certainty in software, it is that your users will always find any bugs you release. Soon, your support team will hear about them – as will the public. When was the last time you bought software (or anything else for that matter) where there wasn’t an accompanying space for user reviews? These days, you get fewer than 4 stars and your app is probably toast.

Enter the software testing professional. Similar to the sales professional, the software testing professional learns to do what he or she used to do as a dummy, only now they do it with purpose and according to a plan – even if the plan isn’t written. The best software testing professionals have a good general knowledge about how software works and about the kinds of mistakes that developers often make when trying to build bulletproof apps.

Sure, a professional is going to run all of the appropriate positive tests – mostly just in case something went wrong in the build. But much more of a professional’s time is going to be spent anticipating what novice users might try or what operating conditions the developer might not have anticipated. The professional will spend most of his or her time in these areas. As we said in our article on the 80/20 rule, the best professionals aren’t merely a little more productive than amateurs as a result. They can be 3 to 5 times as productive.

But Aren’t Professionals Expensive?

You might be thinking, “So why shouldn’t I only hire dummies? My company could save a lot of money.” This is a very good question. At first blush, this would seem to make sense.

But remember that while dummies do indeed find more bugs than amateurs, they find them by stumbling across them. In other words, the bugs they find (and the ones they miss) will be a matter of pure random chance. And since they are inexperienced in software testing, they often won’t know what caused a bug and won’t be able to repeat it, much less to write up a bug report that allows the development team to reproduce and fix it.

But wait, there’s more. Hiring only dummies can have even more dire consequences. If you try to build your testing organization with no professionals, your dummy testers will all naturally “grow” into amateurs. Without mentoring from professionals, there is a risk that they will literally never progress beyond the amateur phase. Unless you can somehow keep them on their toes by constantly having them test unfamiliar software, you’ll end up with a team of amateurs – the worst of all worlds: “experienced” testers that miss most of your bugs.

So How Do Testers Ever Become Professionals? And How Can I Find Them?

We talked a little bit about this in our previous article on the 80/20 rule. You can get a long way down the professional QA road by hiring the right people and measuring and rewarding the right metrics. But as you might expect, a more satisfying answer to this question will require more than another paragraph or two to answer – at least in any truly helpful way. So stay tuned and we’ll do our best to offer a few more thoughts along these lines in a future article.

Oh, and by the way, one reason you never want a developer testing his or her own work is that developers are always QA amateurs when testing their own code. By definition, nobody can see his or her own blind spots.